The Beast (for Artificial Intelligence)

Project type:

Movie promotion

In support of:

Artificial Intelligence (Dreamworks)

Agency:

Microsoft Game Studios

Date:

Spring 2001

Description:

The web campaign for Steven Speilberg's Artificial Intelligence was a watershed event in immersive marketing. The basic idea was to generate buzz about the movie by telling a web-based murder mystery involving humans, robots, and a variety of other forms of artificial intelligences. But The Beast, as the event became known, went far beyond simply telling a story as one ordinarily thinks of storytelling.  This wasn't a matter of simply going to a web site and reading the story. Rather, The Beast used the web and a wide range of Internet and communication technologies to create a seemingly-real event on the web, taking the form of something between a story and a game.

This wasn't a matter of simply going to a web site and reading the story. Rather, The Beast used the web and a wide range of Internet and communication technologies to create a seemingly-real event on the web, taking the form of something between a story and a game.

To really understand what was going on in the story, you had to immerse yourself in a vast collection of media -- over 35 websites representing people and organizations in the game, an ongoing stream of e-mail messages, phone calls, and faxes from characters, and a continuing collection of in-person events, puzzles, TV commercials, print ads, billboards, and cast/crew interviews. At its most basic level, the "point" of The Beast was to tie together all this information and solve the mystery, but, at another level, the real point was to understand and get involved in the story created by the team, just as one would get involved in a traditional piece of literature. The event's web sites received over a million visitors, and the event -- and thus the movie it was promoting -- received a huge amount of press.

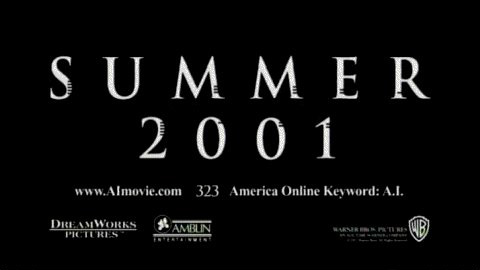

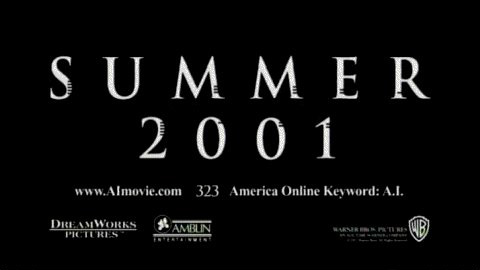

The Beast was never explicitly announced or advertised as such. The sites making up The Beast were never actually identified as being part of a work of fiction or even as having any direct connection to the movie; they simply showed up on the Web, with enough clues to lead the game-players from one site to the next. The event was launched through clues planted in the initial TV commercial for the movie, which included a reference to Jeanine Salla as the movie's "Sentient Machine Therapist". Doing a web search for Salla revealed her personal website as well as the site for her employer, Bangalore World University. In addition, the final frame of the commercial showed the words Summer 2001 which, if you looked carefully, had some rather odd notches cut into the letters. Counting the notches on the letters produced a phone number which, when called, yielded a voice message suggesting an address to which an e-mail might be sent, which produced a response with a pointer to another website, and so on. As more and more clues were found, the story of the murder of Evan Chen began to become clear, although the identity of the murderer and the reason for the murder were far less clear.

The event was launched through clues planted in the initial TV commercial for the movie, which included a reference to Jeanine Salla as the movie's "Sentient Machine Therapist". Doing a web search for Salla revealed her personal website as well as the site for her employer, Bangalore World University. In addition, the final frame of the commercial showed the words Summer 2001 which, if you looked carefully, had some rather odd notches cut into the letters. Counting the notches on the letters produced a phone number which, when called, yielded a voice message suggesting an address to which an e-mail might be sent, which produced a response with a pointer to another website, and so on. As more and more clues were found, the story of the murder of Evan Chen began to become clear, although the identity of the murderer and the reason for the murder were far less clear.

This event ran for four months leading up to the release of the movie in May 2001; new clues were released on a regular basis to move the story ahead and keep the participants involved. Only at the end of the event was any public acknowledgment of its real nature and its creators made. There was so much taking place in the event, and what was taking place was often so complex, that it's doubtful that any single person could have comprehended it all. As a result, an informal, web-based group, Cloudmakers emerged as a community of people interested in following The Beast. Its website, still active, became the best place to go to share information, theories, and guesses about what the latest bits of information meant. This is not the place to try to summarize the story told by The Beast; I'll point interested people to Cloudmakers for an incredibly detailed summary of the event, and an archive of all the event's sites (most of whose original installations have since fallen off the web).

Having paid due homage to The Beast, let me step back for a minute and try to be objective about its value as a promotional tool. Like most groundbreaking things, The Beast may ask more questions than it answers. Some of the questions I have would include:

This wasn't a matter of simply going to a web site and reading the story. Rather, The Beast used the web and a wide range of Internet and communication technologies to create a seemingly-real event on the web, taking the form of something between a story and a game.

This wasn't a matter of simply going to a web site and reading the story. Rather, The Beast used the web and a wide range of Internet and communication technologies to create a seemingly-real event on the web, taking the form of something between a story and a game. To really understand what was going on in the story, you had to immerse yourself in a vast collection of media -- over 35 websites representing people and organizations in the game, an ongoing stream of e-mail messages, phone calls, and faxes from characters, and a continuing collection of in-person events, puzzles, TV commercials, print ads, billboards, and cast/crew interviews. At its most basic level, the "point" of The Beast was to tie together all this information and solve the mystery, but, at another level, the real point was to understand and get involved in the story created by the team, just as one would get involved in a traditional piece of literature. The event's web sites received over a million visitors, and the event -- and thus the movie it was promoting -- received a huge amount of press.

The Beast was never explicitly announced or advertised as such. The sites making up The Beast were never actually identified as being part of a work of fiction or even as having any direct connection to the movie; they simply showed up on the Web, with enough clues to lead the game-players from one site to the next.

The event was launched through clues planted in the initial TV commercial for the movie, which included a reference to Jeanine Salla as the movie's "Sentient Machine Therapist". Doing a web search for Salla revealed her personal website as well as the site for her employer, Bangalore World University. In addition, the final frame of the commercial showed the words Summer 2001 which, if you looked carefully, had some rather odd notches cut into the letters. Counting the notches on the letters produced a phone number which, when called, yielded a voice message suggesting an address to which an e-mail might be sent, which produced a response with a pointer to another website, and so on. As more and more clues were found, the story of the murder of Evan Chen began to become clear, although the identity of the murderer and the reason for the murder were far less clear.

The event was launched through clues planted in the initial TV commercial for the movie, which included a reference to Jeanine Salla as the movie's "Sentient Machine Therapist". Doing a web search for Salla revealed her personal website as well as the site for her employer, Bangalore World University. In addition, the final frame of the commercial showed the words Summer 2001 which, if you looked carefully, had some rather odd notches cut into the letters. Counting the notches on the letters produced a phone number which, when called, yielded a voice message suggesting an address to which an e-mail might be sent, which produced a response with a pointer to another website, and so on. As more and more clues were found, the story of the murder of Evan Chen began to become clear, although the identity of the murderer and the reason for the murder were far less clear. This event ran for four months leading up to the release of the movie in May 2001; new clues were released on a regular basis to move the story ahead and keep the participants involved. Only at the end of the event was any public acknowledgment of its real nature and its creators made. There was so much taking place in the event, and what was taking place was often so complex, that it's doubtful that any single person could have comprehended it all. As a result, an informal, web-based group, Cloudmakers emerged as a community of people interested in following The Beast. Its website, still active, became the best place to go to share information, theories, and guesses about what the latest bits of information meant. This is not the place to try to summarize the story told by The Beast; I'll point interested people to Cloudmakers for an incredibly detailed summary of the event, and an archive of all the event's sites (most of whose original installations have since fallen off the web).

Having paid due homage to The Beast, let me step back for a minute and try to be objective about its value as a promotional tool. Like most groundbreaking things, The Beast may ask more questions than it answers. Some of the questions I have would include:

- The event vs. the publicity of the event. Befitting the watershed nature of The Beast, a huge amount of press coverage sprang up the event itself -- the fact that Dreamworks was using this crazy web thing to promote their movie. This was great for Dreamworks, but it muddies the issue for those of us who are trying to figure out the value of these kinds of campaigns. It's now three years later, and immersive campaigns (albeit smaller-scale) have become common enough that you can't count on press coverage of the fact that you're running one for your movie. How much buzz about the movie came from The Beast itself, rather than the publicity about The Beast? Independent of the benefit of the press coverage, would The Beast's budget have been better spent on spot TV and print runs? We're still finding out.

- How much complexity is enough? The Beast was a very complicated event, one that was easily capable of demanding several hours a day to work through the latest round of clues and puzzles. While a large number of people might have spent a few minutes looking around Jeanine Salla's website or one of the other well-publicized sites, the hard-core Beast fans were far fewer in number. There were 7,000 registered members of Cloudmakers, and an even smaller group of those people provided the bulk of activity on the site. I followed it as closely as I could, but I must confess I simply ran out of free time, and fell out of contact with the event about halfway through -- I still don't know who killed poor Evan Chen.

So, again, we get into questions of return on investment. Looking at The Beast purely as a promotional device, I'm inclined to think that a simpler and less-elaborate event would have produced the same amount of promotional interest in the movie, at far less cost. Of course, Microsoft is a rich enough company that budget may not have been the first issue on their minds, especially if one of the reasons for doing The Beast was to explore the viability of these kinds of events as a future line of business for the Game Studio. And thinking about The Beast as something akin to a video game raises different questions -- who's your audience, and what's the right level of complexity for them? Do you skew towards complex in search of the hard-core gamers, who have demonstrated their willingness to devote lots of time to arcane details? Or do you skew towards simple, in search of a broader and larger audience? The ilovebees event may give us some useful information on this -- it's a promotional event focused on gamers, so the complexity and time demand of the event may be a good match to its audience. Meanwhile, from a promotional perspective, the ROI question continues to impact those of who have to live with limited budgets and look for the biggest impact we can get with them.